In the 1950s, the American Southwest became a crossroads for abstract expressionists from New York and San Francisco. Beatrice Mandelman (American, 1912-1998) and Louis Ribak (American, b. Lithuania, 1902-1979) were two of the most influential in the creation of the group known as the Taos Moderns, including renowned artists Agnes Martin and Edward Corbett, among others.

The artists had met and married in New York and made their way to the Southwest, settling in Taos, New Mexico in 1944. Not only were they at a new nexus of artistic collaboration and cross-pollination, but the landscape and local cultures of New Mexico pushed Mandelman and Ribak into unexplored stylistic realms grounded in abstraction. They established a lifelong practice and livelihood in the Southwest, opening a gallery space out of their home, establishing the Taos Valley Art School, and leaving behind a legacy of thousands of original artworks inspired by the light, shape, color, and form of the desert-scape.

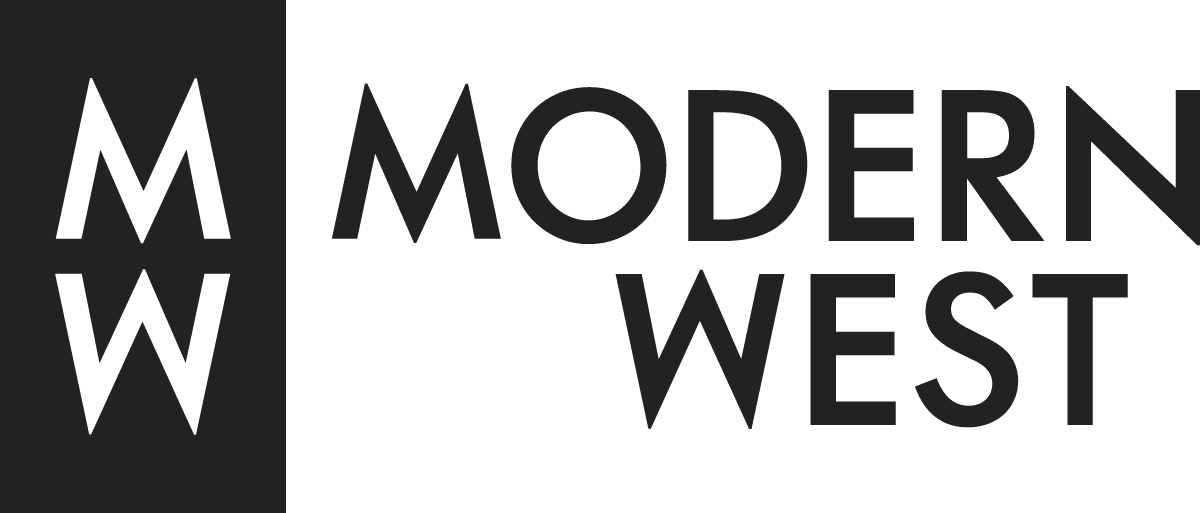

Beatrice Mandelman, known to many as Bea, lived a life dedicated to art. Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1912, the young artist began her studies at Newark’s School of Fine and Industrial Arts, yet it was her connections to Louis Lozowick and Willem de Kooning that were likely even more influential in her early development. In 1924, when Mandelman was only twelve, it was Lozowick’s vast knowledge of Constructivism (gained from a four-year sojourn abroad) that ignited Mandelman’s sustained interest in the European avant-garde. De Kooning was equally significant. After meeting the recent émigré in the late 1920s, Mandelman became a regular in the artist’s studio, listening with rapt attention to his lively discussions with Arshile Gorky and others within the burgeoning New York art scene.

While the influence of their Modernist aesthetics would be felt decades later, Mandelman’s early works embraced the social realism brought on by the Great Depression. In 1935, she became one of the thousands of artists employed by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Arts Project, serving in its mural and graphic arts divisions. Mandelman’s impressive serigraphs from this period gained considerable attention and were presented at both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art.

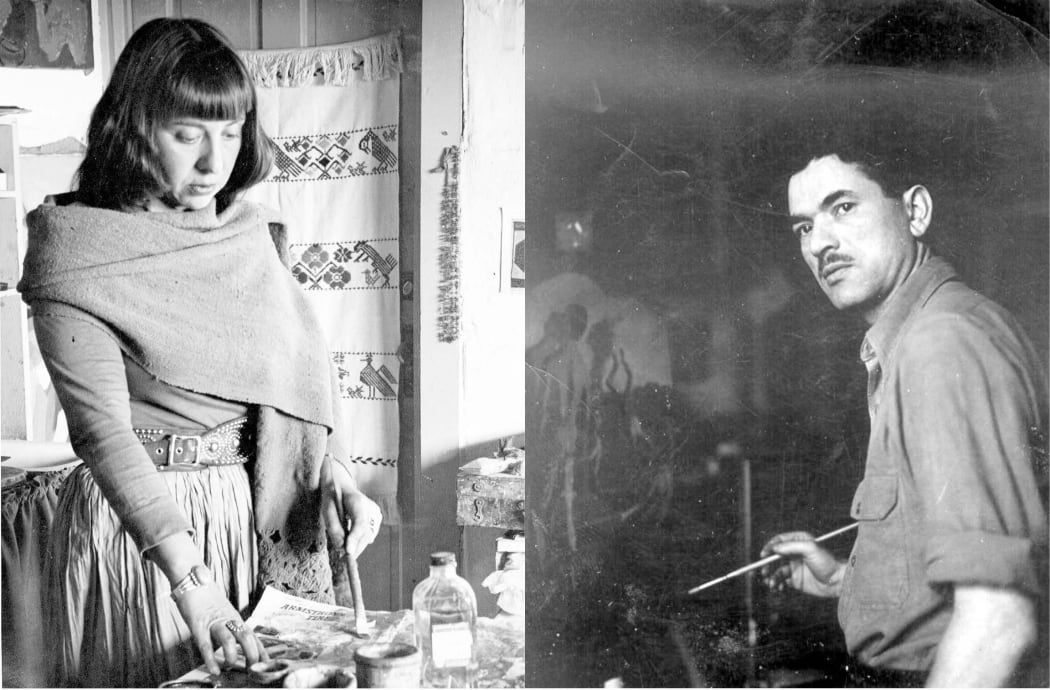

In 1942, Mandelman married fellow artist Louis Ribak, a highly-regarded social realist painter. Two years later, despite the great success that each was having in New York, they decided to leave the growing metropolis. Ribak’s health counted among the reasons, as did the FBI. Indeed, Mandelman and Ribak had substantial ties to leftist publications and associations, leading to unwanted scrutiny by the federal government. In 1944, during a trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico, the two artists ventured further to Taos and it was in this small town that they embraced a new life.

Taos, while rugged and remote, had distinguished itself as a destination for artists since the late nineteenth century. The Taos Society of Artists was founded in 1915, and included academic figurative artists drawn to the Puebloan culture. The awe-inspiring nature of the landscape(and the pull of wealthy arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan) had also drawn visitors like Ansel Adams and Georgia O’Keeffe. Mandelman and Ribak, meanwhile, emerged as the nexus of a new generation of artists—one who created an unexpected center of Modernism in the deserts of New Mexico.

Mandelman’s and Ribak’s evolution from social realism to abstraction was not immediate, but was underway by the late 1940s. This transition was spurred by Mandelman’s studies under Fernand Léger in Paris in 1948, as well as an influx of new ideas brought by the students attending Mandelman and Ribak’s Taos Valley Art School, which had opened in 1947. Their students, coming from the east and west coasts, shared the seminal developments of Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Josef Albers, and others. By the 1950s, Taos had become home to numerous Modernists, Agnes Martin among them, and the group as a whole became known as the Taos Moderns. Mandelman and Ribak were integral in starting artist cooperatives and galleries that would support this growing community.

By the mid-1960s, many of the Taos Moderns had departed, but Mandelman and Ribak stayed. Their close ties to the landscape in Taos continued to subtly influence their particular inflection of Modernism, which strengthened and evolved over the following decades until Ribak’s death in 1979 and Mandelman’s in 1998. Their enduring legacy is one of dedication—to a place, to a visual language, and to one another.

Seeking essence above realism, Mandelman exploited the expressive possibilities of elemental form and color in her work. Her compositions are vibrant and full of energy, often with a densely-packed network of overlapping geometric and organic shapes. While this style of abstraction can sometimes feel haphazard, Mandelman’s work displays thoughtful consideration of the interplay between adjoining forms and colors and between individual parts and the whole. There is playfulness in her approach, but also purpose and restraint. Returning to Red and Blue as an example of her meaningful gestures full of deliberate dissonance, geometric shapes abut the organic, clean edges abut inexact hand-drawn lines, and subtle hints of color activate the edges and interstices of this complex amalgam of forms.

When compared to the work of Louis Ribak, Mandelman’s husband and fellow Taos Modernist, the enduring—and fascinating—creative conversation between the two artists comes into view. The relationship between Dark Noon and Blue Circle, or Sun Series B6 and Jugglers, illustrates their shared approach towards elemental form and color. There are, of course, also noteworthy differences Mandelman’s use of collage created a textural element that is absent in Ribak’s work, and Ribak’s pared down approach to composition stands in contrast to Mandelman’s more densely-packed style. Still, their Modernist experiments were a shared pursuit, with ideas around form and color reverberating in a back and forth exchange.

Mandelman and Ribak’s distinct palette included a wide use of primary colors frequently joined by pinks, peaches, and browns, all in tones that were particularly attuned to the natural world. (This dialogue with the landscape was furthered on occasion through the titles that each artist assigned to their works.) Even more striking, however, is their use of the color white. Creating an almost jarring sense of light and space, it served to draw attention to the indeterminate ground of some works, shifting between positive and negative space. White plays a dominant role in works like Number 7, but it also acts more subtly in Mandelman’s Yellow No. 2 and Ribak’s Blue and Peach Abstract.

As in other works by Ribak, Blue and Peach Abstract demonstrates the particular attention—through form and color—that the artist brought to the edges of his compositions.

Enlivened with visual drama and tension, Mandelman’s and Ribak’s works of the 1960s and 1970s are undeniably alluring. Mandelman particularly celebrated this dissonant, off-center quality:

“Off center means to me that a person has to give my work thought, it has to be looked at, it has to be given energy.” Both Mandelman and Ribak, in their highly sophisticated play with form and color, created works that reward energy, offering subtle yet compelling details that emerge with time.